The hippocampus (from the Ancient Greek ἱππόκαμπος, literally ‘sea-horse’), is a hybrid mythological creature which combines a horse’s head and a serpentine or fish body, often with wings. It was a common motif in Greek and Roman mythology, but it also appears on Egyptian material from the Late Period onwards.

Within classical mythology, the hippocampus often appeared alongside sea gods such as Poseidon or Neptune, with Homer describing Poseidon driving a chariot of sea-horses across the waves in battle. In Etruria, hippocampi appear on tomb walls and reliefs, often winged, and may link to the idea of voyaging to the afterlife. The creatures also appear on Greek vases, as well as Roman mosaics and oil lamps, suggesting consistency in the presence of hippocampi as mythological motifs throughout several ancient cultures. While hippocampi are traditionally viewed as sea horses, in Egyptian examples, they appear to be more fantastical creatures, presented as serpents with horse-heads, rather than specifically related to sea gods or marine myths. Hippocampi begin to appear in Egyptian art from the beginning of the Late Period (664 BC) onwards, with examples found on coffin lids and cartonnage (Figs. 1 and 2). It is possible that they were introduced during this period as a result of cultural assimilation and entanglement between Egyptian cultures and the Mediterranean during this period.

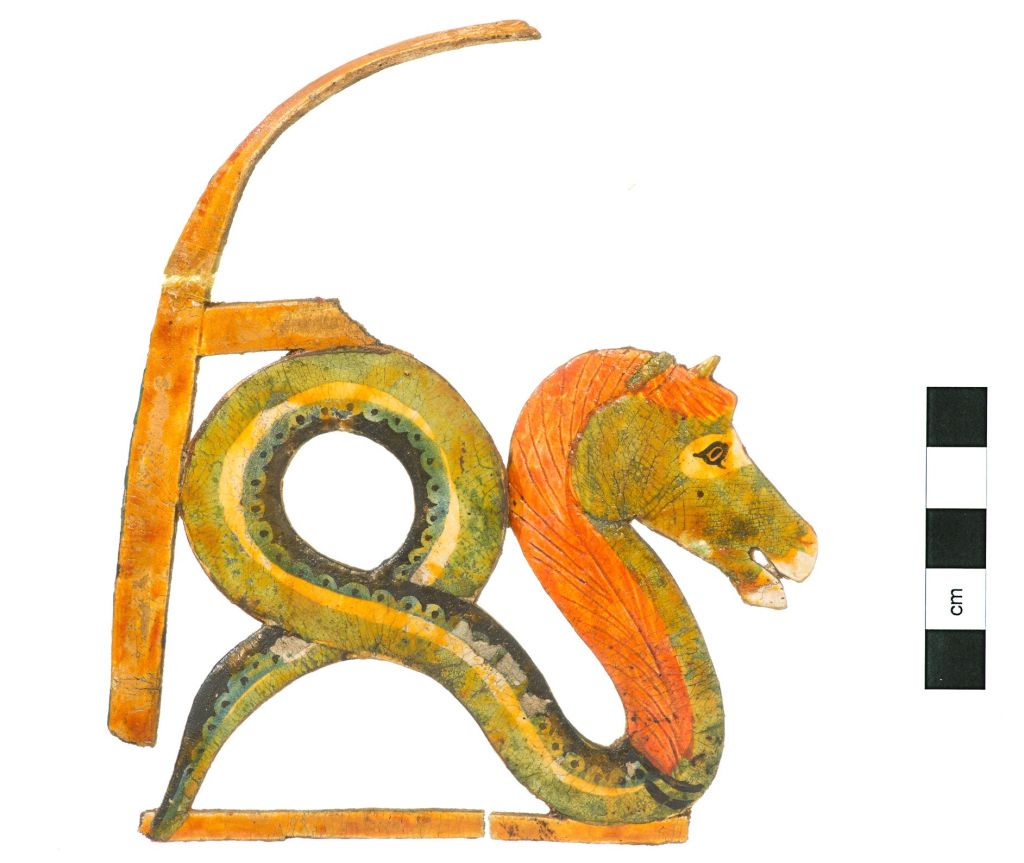

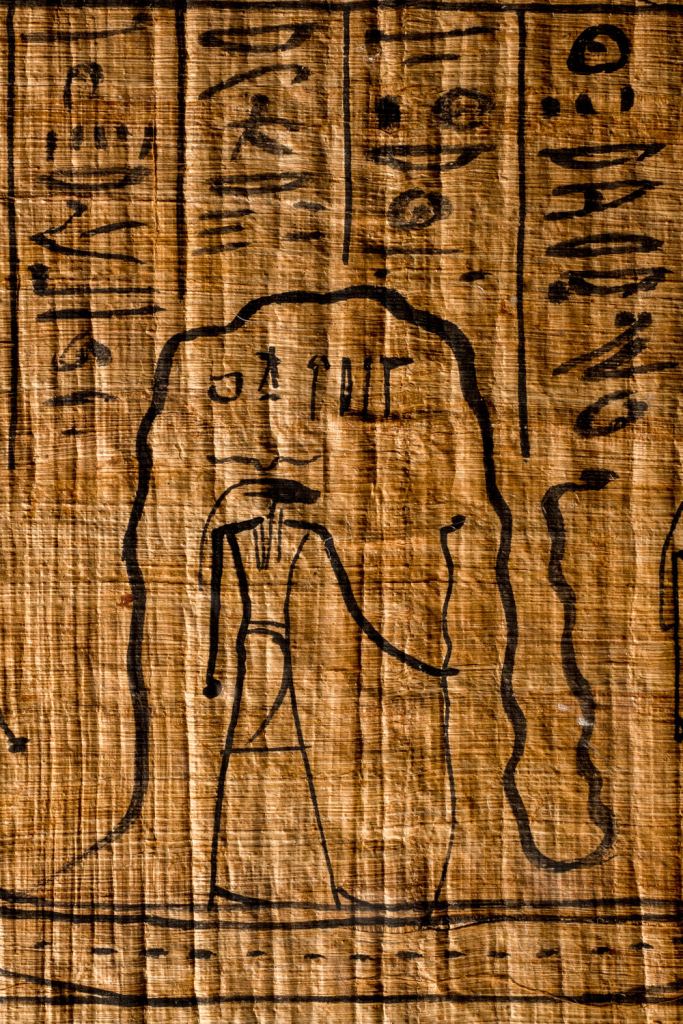

For example, a hippocampus appears on a Late Period coffin lid, painted with red details and flanked by two winged goddesses. This hippocampus is more serpentine in shape than the classical winged appearance it usually displays, and appears coiled on a boat or barque, covering a solar disc and acting as a protector. This type of presentation bears striking resemblance to earlier depictions of Khnum being protected by the serpent Mehen on the solar barque. This depiction may also link to the idea of hippocampi as protectors of those travelling to the afterlife, as seen in Etruscan mythology. In ancient Egyptian myth, snakes could act as protectors, with the rearing cobra taking pride of place on royal crowns as a uraeus, and protective demons such as Mehen encircling Re on his nightly journey (see Fig. 3). The second example of a hippocampus in the Garstang collection is made of cartonnage, is brightly painted, and was likely part of a larger piece. The creature is depicted in the same way as the example from the coffin, with a horse head and mane, and a longer serpentine body that is coiled.

Flanking the hippocampus on the coffin, the goddesses Isis and Nephthys protect the boat in the form of winged serpents, again emphasising the importance of snakes as protectors. While Isis more commonly appears as a winged female goddess, she occasionally is depicted as a snake, for example as Isis-Thermouthis in a Graeco-Roman Period funerary stela (Fig. 4). This hybrid appearance, as a serpent with the head of a woman, further emphasises how animal imagery is utilised in Egyptian art. It is likely that such depictions of hybrid gods and mythological creatures gained popularity from the Late Period onwards due to the growing connections between Egypt and the Mediterranean world, with elements of Greek myth and hybrid gods such as Isis-Thermouthis and Serapis being introduced.

Ultimately, these depictions illustrate how changes in cultural environment, such as introduction of classical myths and ideas through trade links and migration, can allow for the introduction of new motifs such as the hippocampus. Despite being a predominantly classical creature, it was introduced into traditional Egyptian funerary cult and took on attributes of protection and transport which we see assigned to serpents throughout the Pharaonic Period. Such animal forms within ancient Egypt, whether they be real creatures such as serpents or horses, or mythological creations like the hippocampus, allowed individuals to display their desires for a safe journey to the afterlife, and illustrate how influences from the Graeco-Roman world could bleed into and affect how these desires were presented.

To learn more about how animals and hybrid creatures were used and depicted in ancient Egypt and Sudan, visit our FREE exhibition ‘Creatures of the Nile‘, open Saturday 4 May – Saturday 5 October 2024 at the Victoria Gallery & Museum, Liverpool.

by Louise O’Brien and Chang Lu.